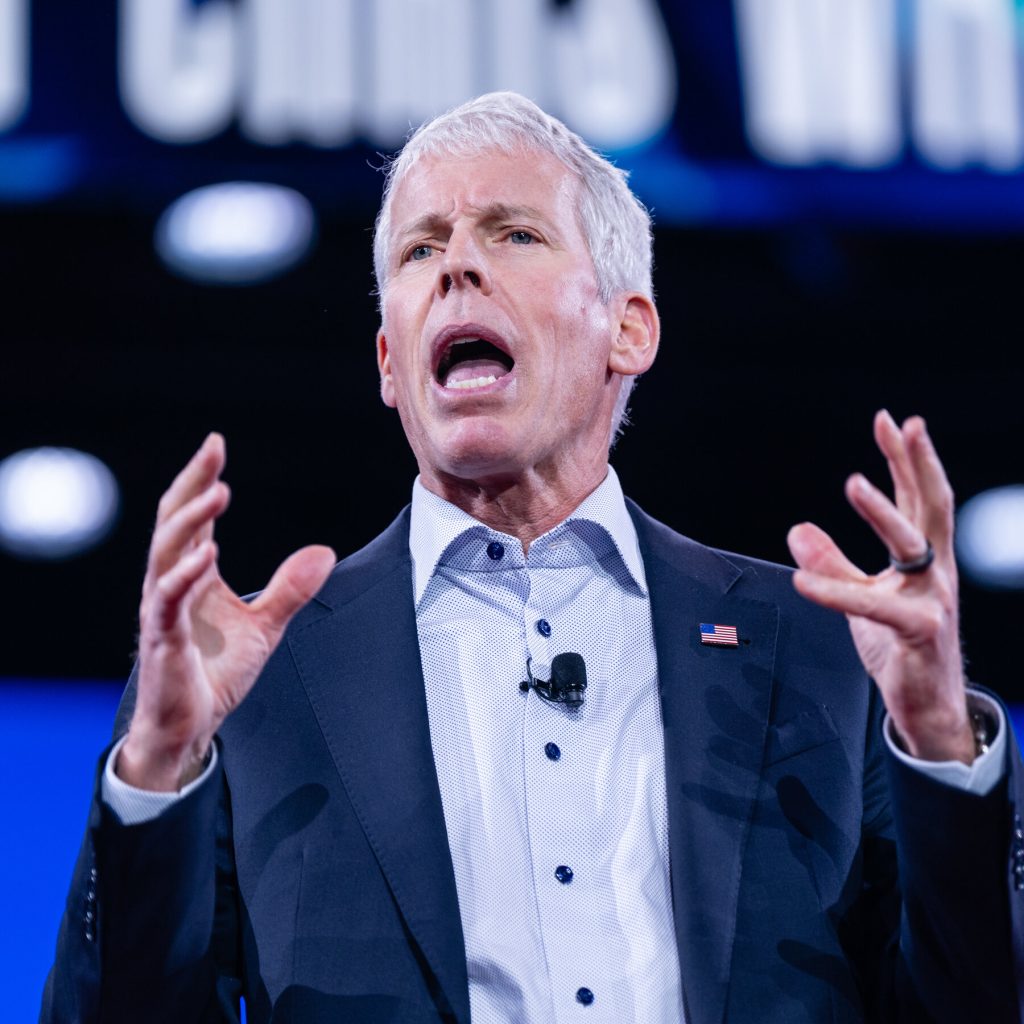

The Contortions of Josh Hawley

For months, no Republican in either the House or the Senate spoke out more forcefully, or more consistently, against cutting Medicaid than Josh Hawley. As President Donald Trump’s “big beautiful bill” was weaving its way through Congress, Hawley argued repeatedly that stripping health insurance from the poorest Americans would be “morally wrong and politically suicidal” for a party that, in the Trump era, has relied on millions of votes from people who receive government assistance. Back home in Missouri, the senator was making the same case in private, according to several people I spoke with who met with him or his staff this year. His deep engagement on the issue impressed advocates representing Missouri’s hospitals, doctors, and rural health centers, all of whom were having trouble getting GOP lawmakers to take their concerns seriously. The changes, these advocates argued, could cost Missouri billions of dollars in federal funding, take away insurance from an estimated 170,000 residents, and force hospitals and rural health centers to close. “I did believe that he was genuine,” Amy Blouin, the president of the Missouri Budget Project, a nonpartisan think tank, told me. “I do see him as a different type of Republican.” Yet Hawley ultimately joined almost every other Republican in Congress and voted for the bill, which independent analysts project will cut nearly $1 trillion from Medicaid and leave 10 million Americans newly uninsured. With three Republicans opposing the legislation in the narrowly divided Senate, Hawley’s support proved decisive. In a statement, Hawley said that the bill’s benefits—chiefly the extension of Trump’s first-term tax cuts—outweighed his concerns. “Gotta take the wins where you can,” the senator told a reporter. Then, last week, Hawley’s Medicaid journey took yet another turn when he introduced legislation that would prevent some of the deepest reductions from taking effect—essentially proposing to repeal a major provision of the legislation he had just voted to enact. [Read: No one loves the bill (almost) every Republican voted for] Hawley’s contortions on the bill were perhaps the starkest illustration of how a Republican Party, under pressure to deliver a quick win for the president, ended up slashing a core social-safety-net program much more deeply than many people expected—and more than some of its own members, including Trump himself at times, seemed to want. Republicans are only now beginning to assess the fallout from their enactment of such a far-reaching law. Polls have found that the bill is unpopular, and its Medicaid cuts especially so. But the law puts off its most painful provisions until after the 2026 midterm elections. Trump himself won’t face voters again, so lawmakers like Hawley will be left to deal with the bill’s political and real-world consequences. Democrats have roundly mocked Hawley, painting him as one more weak-kneed Republican who talked a big populist game on Medicaid only to fold quickly under pressure from Trump. “It was a performance worthy of a gold medal in political pretzel gymnastics,” Russ Carnahan, a former Missouri representative in Congress who is now chair of the state Democratic Party, told me. Hawley’s effort to immediately restore the cuts, Carnahan said, was a cynical attempt to fool Missourians: “He turned his back on helping people when he had the chance.” A former three-term Republican senator from Missouri, John Danforth, was barely more sympathetic. Danforth was once a political mentor to Hawley but broke with him after he backed Trump’s attempt to overturn the 2020 presidential election. He told me that Hawley’s new legislative proposal is tantamount to a press release. “It has no real consequence,” Danforth said, dismissing the measure as “simply a way of saying ‘whoops.’” Hawley’s office declined to make him available for an interview. Instead, a spokesperson pointed to victories that the senator had secured in the GOP bill, including additional relief for Missourians living with cancers linked to Manhattan Project work that took place in the state more than 80 years ago. This morning, at an event hosted by Axios, Hawley said he had drawn a “red line” on benefit cuts for individual Medicaid recipients, and that the bill did not contain any. Hawley had seemed to be an unlikely savior for those looking for a Republican willing to thwart Trump’s agenda. Outside Missouri, he is best known as the senator who held up a fist of support for the Trump faithful storming the Capitol on January 6, 2021, and then, hours later, was seen on video fleeing the same mob. Unlike moderate Senators Susan Collins of Maine and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, Hawley does not have an extensive record of breaking with Republicans on key votes. Nor does he have an imminent campaign to consider; Hawley won reelection last fall by nearly 14 points. The Missourians I spoke with presume that Hawley’s populist rhetoric reflects his national ambitions. With an eye toward the 2028 presidential race, he might be trying to stay loyal to Trump—a requirement for political survival in today’s GOP—while separating himself from rivals whose emphasis on fiscal austerity alienates the president’s working-class supporters. Hawley cited Trump’s own past pledges to protect Medicaid in explaining his initial opposition to the cuts, and he was one of a few Senate Republicans who publicly welcomed the idea (which the party ultimately abandoned) of raising taxes on the rich in the GOP megabill. The bill contains several major changes to Medicaid, and Hawley is trying to prevent only some of them. He continues to support, for example, the work requirements for nondisabled adults that could add administrative burdens to the program and result in millions of people losing insurance. The cuts that Hawley opposes would affect the amount of money that states such as Missouri could receive from the federal government for Medicaid. Hawley has taken credit for the fact that the enacted bill delays the start date of those provisions until at least 2028, and for securing a $50 billion rural health fund in the bill that could partially offset the loss of federal money for states. His