CEA: “Imported Goods Have Been Getting Cheaper Relative to Domestically Produced Goods”

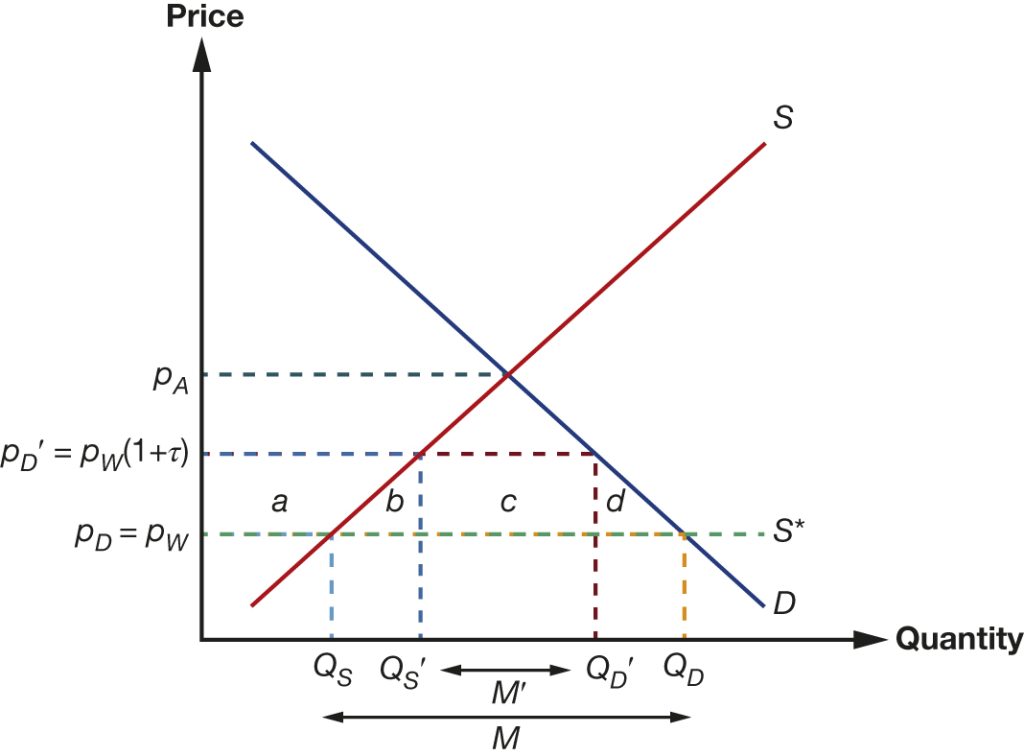

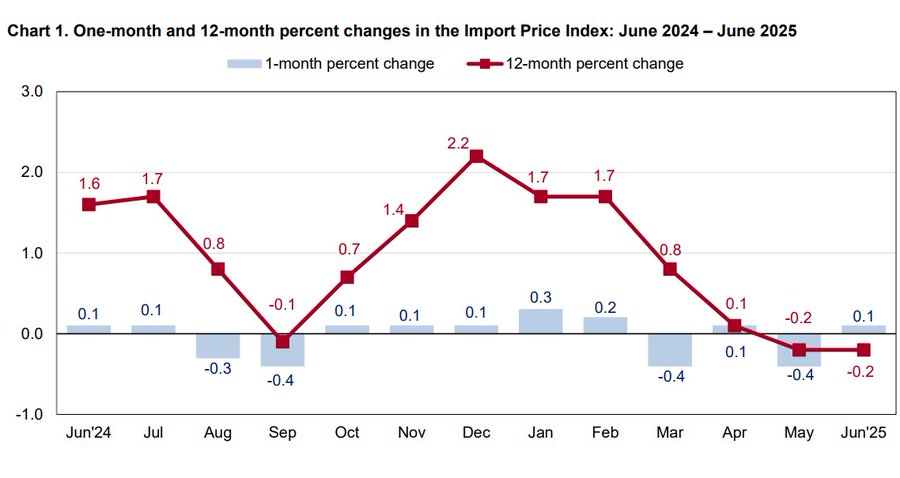

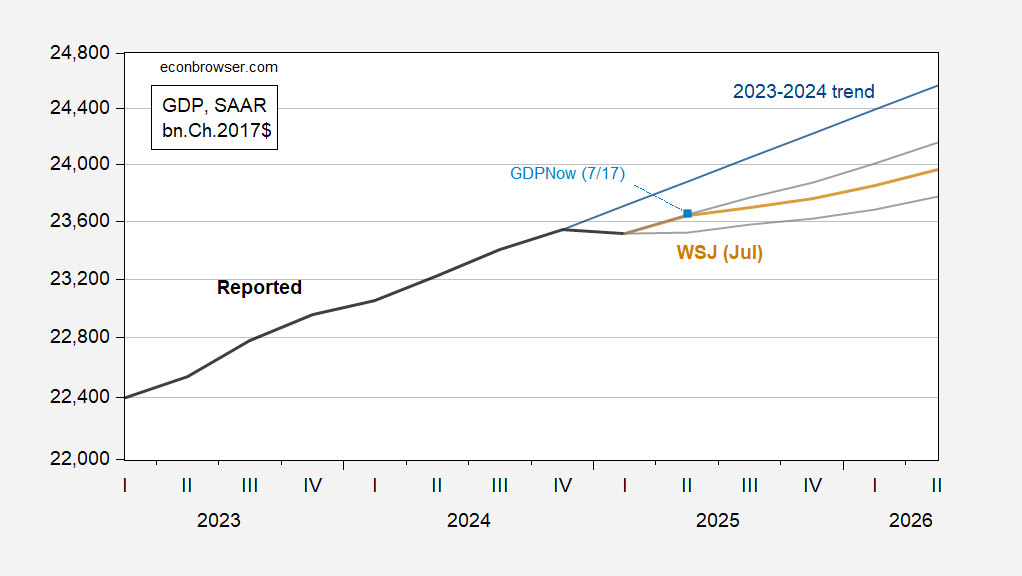

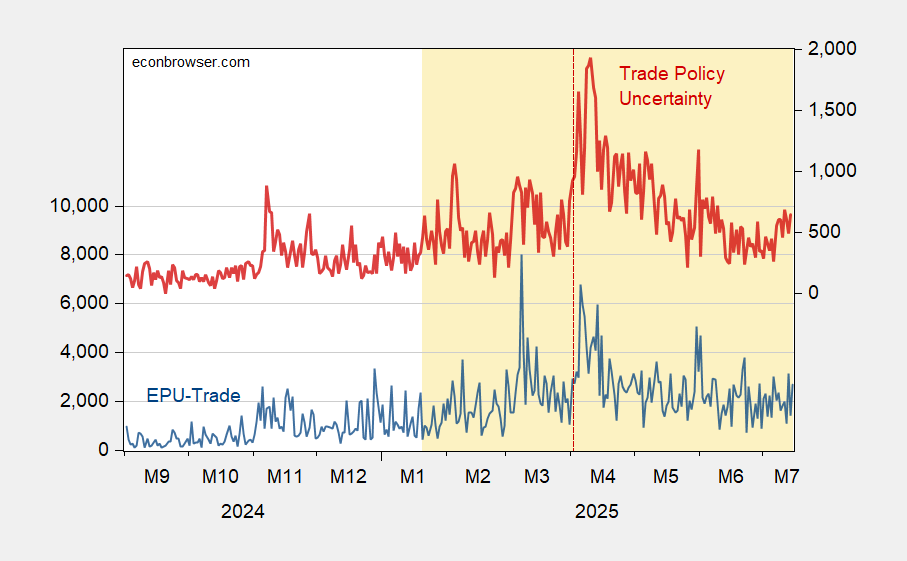

That’s the title of a report by the Trump administration CEA earlier this month. It’s an interesting question whether this is the relevant question or not. What the CEA analysis does is to use the 2017 Input-Output tables to determine what the final goods prices (in CPI or PCE deflator) do, taking into account the amount of imports used in each category. This seems like a reasonable way to proceed, until one thinks about how tariffs work. Consider the simplest case, where the US is a small country. Source: Chinn and Irwin, International Economics (2025). Then using the methodology of the Trump CEA, the importance of tariffs for final demand prices is denoted by M×(Pw(1+τ)-Pw.) [I hold import quantity at pre-tariff level M because CEA uses 2017 IO tables]. However, as is known from basic economics (like the kind one learns in first course econ in undergrad, or even high school), import competing domestic firms also raise their prices. Hence, the prices are raised for quantity M, as well as quantity Qs. In the figure above, this doesn’t change much. However, consider an alternative, where domestic production is much larger relative to imports: Now, price increases apply to quantities 0 to Qs and M. In other words, a much larger share of final production. In other words, the CEA calculations are ignoring the presence of domestic alternatives. For some products (think coffee), there is virtually no domestic production. But for others, there are. Consider steel — Nucor raised their prices when tariffs were announced, even before they were implemented. By the way, if the imported goods are durables, I would expect that domestic, import-competing firms would raise their prices before tariffed goods entered (recall, the universal 10% tariff was only implemented in April, and the CEA analysis applies to final prices through May). The CEA report cites a Fed analysis which uses similar methodology to theirs. I will merely observe that in the case of imported Chinese goods, there are fewer import-competing domestic firms, so the preceding critique need not apply as forcefully.