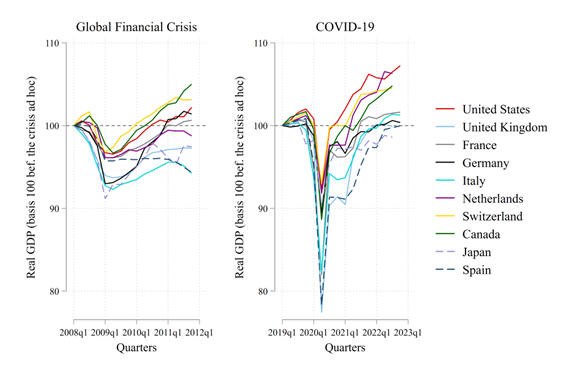

Today, we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Jamel Saadaoui (Université Paris 8-Vincennes). This post is based on the paper of the same title (Aizenman, Ito, Park, Saadaoui, and Uddin, 2025). 1. Introduction During the past 20 years, the world economy suffered two major crises: the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 (the GFC hereafter) and the pandemic crisis (the COVID-19 hereafter) of 2019-2020. A common denominator between the two crises is that both impacted the entire world rather than just one region or one group of countries. In Aizenman et al. (2025), we analyze the patterns of recessions and recoveries of 101 advanced and developing economies, identifying the turning points of recessions and expansions between 1990 and 2022, and perform cross-country analysis of domestic and external drivers of economic recovery. In addition to the standard independent variables, we include institutional development, political stability, the extent of democracy, and trade restrictions indexes and explore their roles in explaining recessions and recovery patterns. Two distinct models of economic recessions can be identified. The first, a Hamiltonian recession, is derived from the pioneering work of James Hamilton (Hamilton, 1989) and foresees recessions that prevent economies from returning to their pre-crisis growth trajectory (see Cerra and Saxena (2008)). This type of recession typically leads to a permanent reduction in an economy’s productive capacity and income level. The second model of recession, conceptualized in modern economic discourse by Milton Friedman (Friedman, 1964, 1993), assumes dynamics known as a Friedman-like recession, which is akin to the response of a stretched guitar string. The further the economy is pushed downward, the more forcefully it rebounds.[1] Productive capacity remains largely intact, and the economy does not suffer a permanent loss of income. The supply side remains resilient, in contrast to the Hamiltonian scenario. Countercyclical monetary and fiscal policies may yield very different results in the two models. To identify economic recessions and recovery, we use the Bry-Boschan (B.B.) algorithm. It automates the cycle-dating procedure in line with the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) tradition (Bry and Boschan, 1971). Using the B.B. algorithm, we identify 419 recessions in our sample of 101 countries over the period 1990-2022. We found that 59 recoveries occurred in 2009 (i.e., the GFC) and 94 occurred in 2020 (i.e., the COVID-19 crisis). Notably, the number of recessions during the COVID-19 crisis is twice as many as during the GFC, illustrating the significant impact of the pandemic. Although many emerging market economies (EME) experienced financial crises in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the number of recessions was not as frequent, suggesting that the crises in emerging market economies were regionally contained. Figure 1. Comparing Two Recoveries: GFC Versus COVID-19 in Industrialized Economies.[2] In Figure 1, GFC seems to have had a longer-lasting impact on this group, with recovery mostly sluggish. For instance, Switzerland and Canada managed to reach their pre-crisis real output level only in the first quarter of 2010. Meanwhile, the peripheral euro-area countries were subsequently hit hard by the euro crisis. On the other hand, the impact of COVID-19 was much bigger than that of the GFC, with Japan and Spain suffering real GDP losses of 20 percent. However, the recovery was also much faster and stronger than during the GFC. The downturn lasted less than two quarters in most cases. For instance, the US and Switzerland managed to recover their pre-crisis real output in the second quarter of 2020. Once again, the recovery was more sluggish for peripheral euro-area countries. In Figure 2, we compare the two recoveries for a selective group of EMEs. In the left panels, we observe that recoveries after the GFC were faster and stronger in EMEs than in IDCs. Since the GFC primarily affected the financial systems and real economies of financially well-developed advanced economies. In the left panel of Figure 2, we observe that the post-COVID-19 recovery pattern was similar for the broader group of EMEs and IDCs. Figure 2. Comparing Two Recoveries: GFC versus COVID-19 in Emerging Market Economies. 2. Regression Results We investigate the determinants of the variables related to recessions and recovery. In addition to the macroeconomic variables identified as important, we include institutional variables based on the principal components (PC) of political risk ratings in the ICRG database. First, we use panel logit models to estimate the probability of an economy entering a recession.[3] Then, given the heterogeneity of our sample economies, we obtain insightful results when we apply a panel logit estimation augmented with interaction terms. Higher levels of holding IR would reduce the probability of a recession, but only for low levels of trade restrictions (i.e., freer trade). This result echoes in the finding of Aizenman, et al. (VoxEU 2023) about the complementarity between the holding of IR and capital account restrictions in the context of terms-of-trade shocks. The buffer effect of IR is only observed when the economy is sufficiently open to trade. When the level of trade restriction is too high, the holding of IR is no longer associated with a reduction of the probability of a recession. When trade restrictions are too high, the buffer effect of macroeconomic variables disappears. Next, we examine whether Hamilton’s or Friedman’s model better depicts the recovery path in the aftermath of a recession. The results suggest that in a stable political environment (Figure 3), recessions during which the GDP decreases by an additional 1 percent induce a stronger output recovery of around 0.9 percent after 4 quarters. The length of the recession has no significant effects on the extent of the recovery 4 quarters later.[4] When the number of trade restrictions is very low (Figure 4), recessions during which the GDP decreases by an additional 1 percent induce a stronger output recovery of around 0.8 percent after 4 quarters. The length of the recession has no significant effects on the extent of the recovery 4 quarters later. Figure 3. Deeper recessions, stronger recoveries? Not always due to political instability. Figure 4. Deeper recessions, stronger recoveries? Not always due