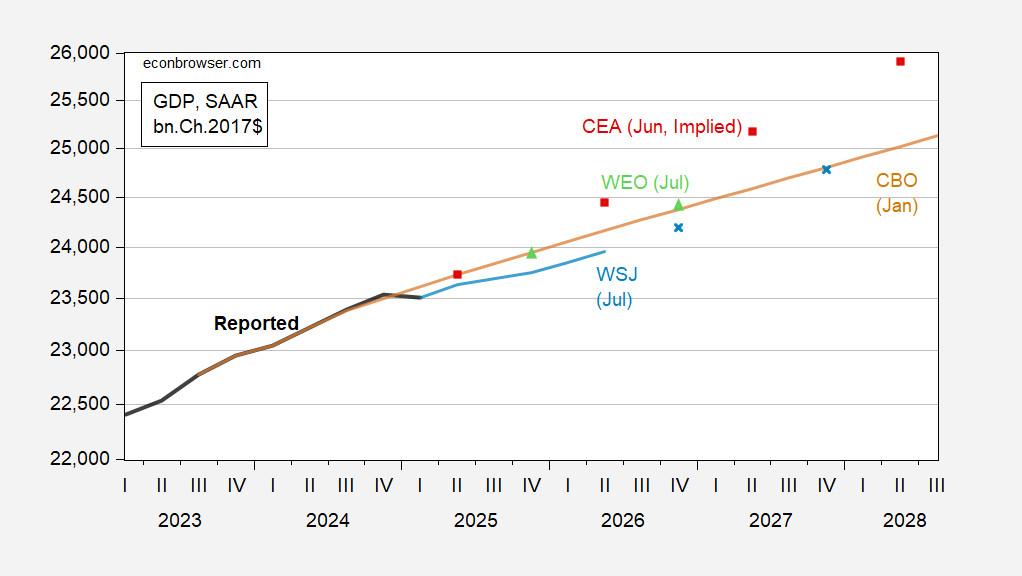

Forecasts: CEA >> IMF > WSJ

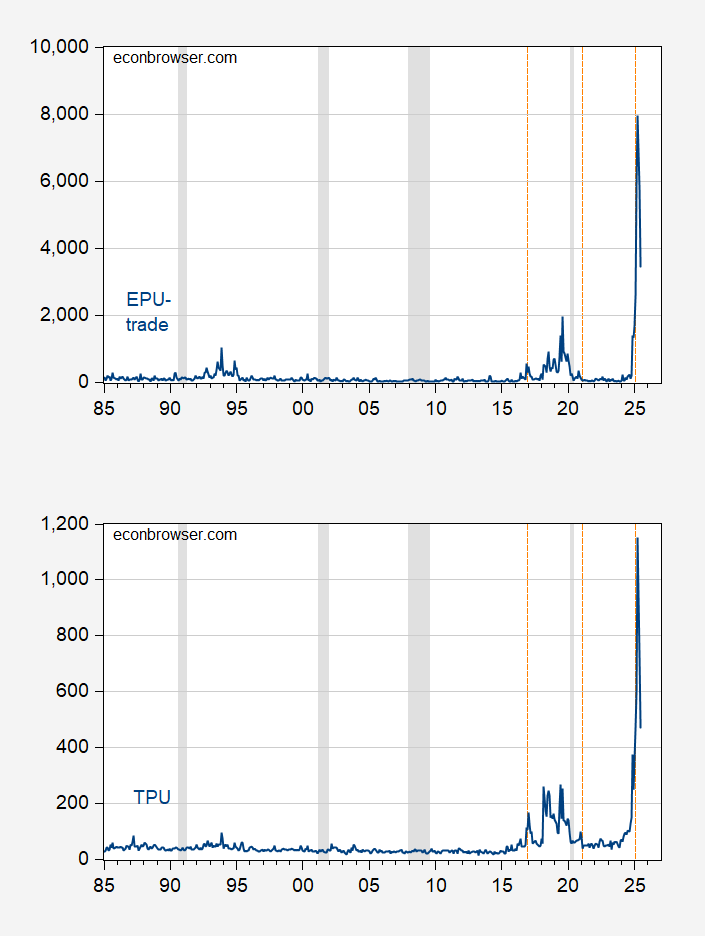

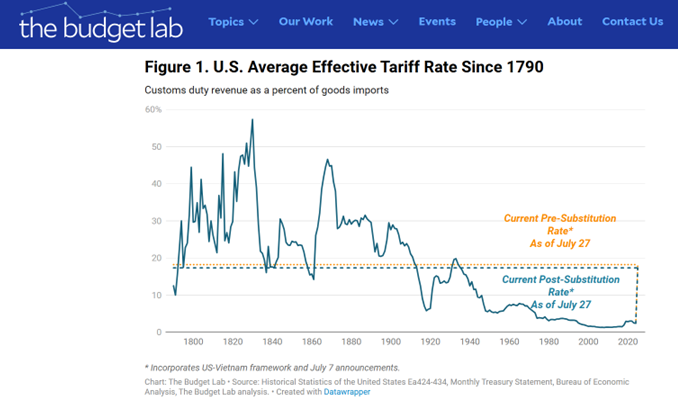

From IMF’s July World Economic Outlook, released today: Figure 1: GDP (bold black), CBO current law projection of January (tan), implied CEA forecast using CBO current law (red squares), mean forecast from July WSJ survey (light blue line, x), July WEO (light green triangle), all in bn.Ch.2017$ SAAR. Source: BEA 2025Q1 3rd release, CBO January 2025, CEA (2025), WSJ survey, and author’s calculations. The IMF WEO trajectory is based on this forecast: Source: IMF, WEO July 2025 update. From the report: Global growth is projected at 3.0 percent for 2025 and 3.1 percent in 2026. The forecast for 2025 is 0.2 percentage point higher than that in the reference forecast of the April 2025 World Economic Outlook (WEO) and 0.1 percentage point higher for 2026. This reflects stronger-than-expected front-loading in anticipation of higher tariffs; lower average effective US tariff rates than announced in April; an improvement in financial conditions, including due to a weaker US dollar; and fiscal expansion in some major jurisdictions. Global headline inflation is expected to fall to 4.2 percent in 2025 and 3.6 percent in 2026, a path similar to the one projected in April. The overall picture hides notable cross-country differences, with forecasts predicting inflation will remain above target in the United States and be more subdued in other large economies. Risks to the outlook are tilted to the downside, as they were in the April 2025 WEO. A rebound in effective tariff rates could lead to weaker growth. Elevated uncertainty could start weighing more heavily on activity, also as deadlines for additional tariffs expire without progress on substantial, permanent agreements. Geopolitical tensions could disrupt global supply chains and push commodity prices up. Larger fiscal deficits or increased risk aversion could raise long-term interest rates and tighten global financial conditions. Combined with fragmentation concerns, this could reignite volatility in financial markets. On the upside, global growth could be lifted if trade negotiations lead to a predictable framework and to a decline in tariffs. Policies need to bring confidence, predictability, and sustainability by calming tensions, preserving price and financial stability, restoring fiscal buffers, and implementing much-needed structural reforms.