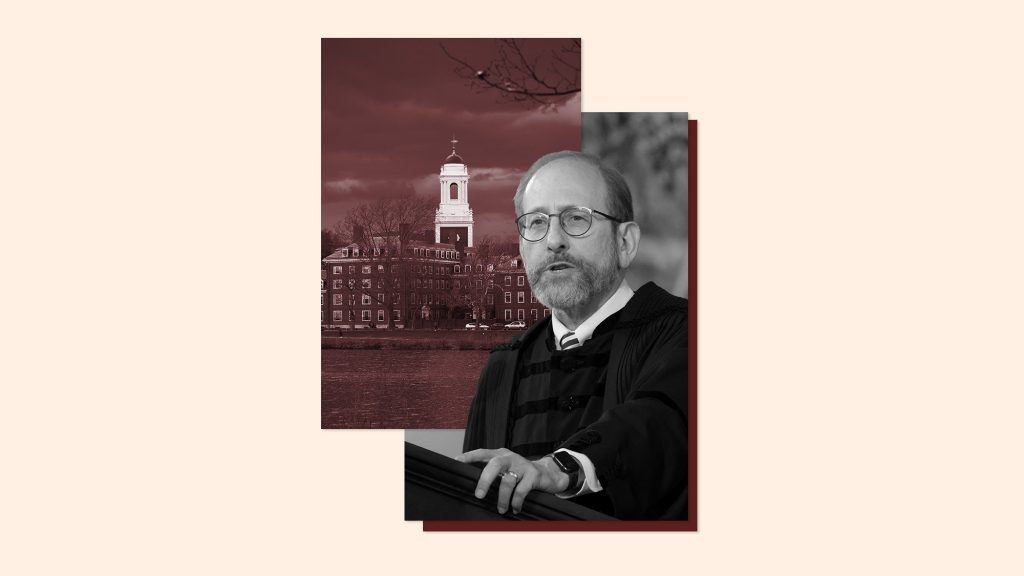

Can This Man Save Harvard?

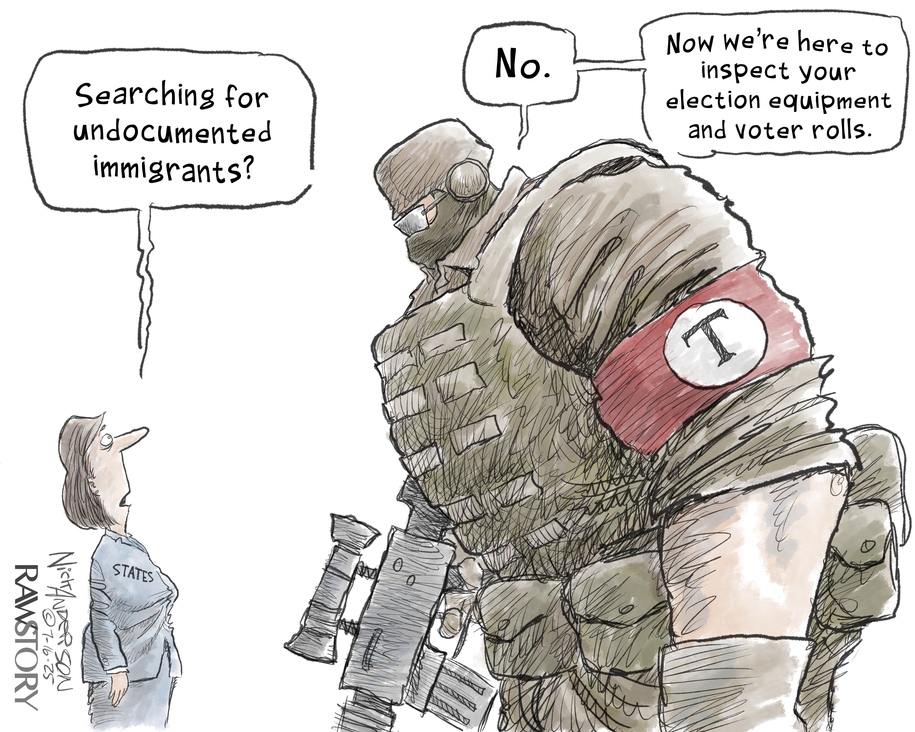

The email landed at 10 minutes to midnight on a Friday in early April—a more menacing email than Alan Garber had imagined. The Harvard president had been warned that something was coming. His university had drawn the unwanted and sustained attention of the White House, and he’d spent weeks scrambling to stave off whatever blow was coming, calling his institution’s influential alumni and highly paid fixers to arrange a meeting with someone—anyone—in the administration. When he finally found a willing contact, he was drawn into aimless exchanges. He received no demands. No deadlines. Just a long conversation about the prospect of scheduling a conversation. Garber wanted an audience because he believed that Harvard had a case to make. The administration had been publicly flogging elite universities for failing to confront campus anti-Semitism. But Garber—a practicing Jew with a brother living in Israel—believed Harvard had done exactly that. In the spring, Garber had watched Donald Trump take aim at Columbia, where anti-Israel demonstrations the previous year had so overwhelmed the campus that the university canceled the school’s graduation ceremony and asked the New York Police Department to clear encampments. In early March, the Trump administration cut off $400 million in federal funding to the school and said that it would consider restoring the money only if Columbia agreed to dramatic reforms, including placing its Middle East–studies department under an auditor’s supervision. Ever since William F. Buckley Jr. turned his alma mater, Yale, into a bête noire, the American right has dreamed of shattering the left’s hegemony on campus, which it sees as the primary theater for radical experiments in social engineering. Now the Trump administration was using troubling incidents of anti-Jewish bigotry as a pretext to strip Ivy League adversaries of power and prestige. The administration’s demands of Columbia impinged on academic freedom. But from Harvard’s parochial vantage point, they were also oddly clarifying. Whatever had gone wrong in Cambridge—and Garber’s own university faced a crisis of anti-Jewish bias—it hadn’t metastasized like it had in Morningside Heights. Harvard had disciplined protesters, and Garber himself had denounced the ostracism of Jewish students. Whichever punishment the administration had in mind, surely it would fall short of the hammer dropped on Columbia. [Franklin Foer: Columbia University’s anti-Semitism problem] That was Garber’s frame of mind when the late-night ultimatum arrived: Submit to demands even more draconian than those imposed on Columbia, or risk forfeiting nearly $9 billion in government funding. Even for Harvard, with a $53 billion endowment, $9 billion represented real money. The email ordered the university to review faculty scholarship for plagiarism and to allow an audit of its “viewpoint diversity.” It instructed Harvard to reduce “the power held by faculty (whether tenured or untenured) and administrators more committed to activism than scholarship.” No detail, no nuance—just blunt demands. To the Trump administration, it was as if Harvard were a rogue regime that needed to be brought to heel. Trump’s team was threatening to unravel a partnership between state and academe, cultivated over generations, that bankrolled Harvard’s research, its training of scientists and physicians, its contributions to national security and global health. Federal funds made up 11 percent of the university’s operating budget—a shortfall that the school couldn’t cover for long. Stripped of federal cash, Harvard would have to shed staff, abandon projects, and shut down labs. Yet the message also offered a kind of relief. It spared Garber from the temptation of trying to placate Trump—as Columbia had sought to do, to humiliating effect. The 13 members of the Harvard Corporation, the university’s governing body, agreed unanimously: The only choice was to punch back. The university’s lawyers—one of whom, William Burck, also represented Trump-family business interests—wrote, “Neither Harvard nor any other private university can allow itself to be taken over by the federal government.” Soon after Harvard released its response, absurdity ensued. The Trump administration’s letter had been signed by three people, one of whom told Harvard he didn’t know the letter had been sent. The message, Garber realized, may have been sent prematurely. Or it may have been a draft, an expression of the White House’s raw disdain, not the vetted, polished version it intended to send. But the administration never disavowed the letter. And over the next three months, the president and his team would keep escalating. On Memorial Day, I met Alan Garber at his home, a 10-minute walk from Harvard Yard. One of the perks of leading Harvard is the right to reside in Elmwood, an imposing Georgian mansion that befits a prince of the American establishment. But Garber had declined the upgrade, choosing instead to remain in the more modest home provided to the university’s provost. When he took the president’s job last year at 69, after 12 years as provost, he agreed to a three-year term; he didn’t want to uproot his life. I was surprised he found time to talk. It wasn’t just a national holiday—it was the start of the most stressful week on a university president’s calendar. Graduation loomed on Thursday, with all its ceremonial burdens: the speechifying, the glad-handing, the presence of the school’s biggest donors. Garber led me into his living room, undid his tie, and slouched into a chair. A health-care economist who also trained as a physician, he carries himself with a calm that borders on clinical. Even an admirer such as Laurence Tribe, a Harvard Law professor, describes Garber as “meek in the way he sounds.” He is the opposite of bombastic: methodical, a careful listener, temperamentally inclined to compromise. But after Harvard’s feisty reply to the administration, Garber found himself cast a mascot of the anti-Trump resistance. This was surprising, because in his 18 months as president, Garber has positioned himself as an institutionalist and an opponent of illiberalism in all its forms: its Trumpian variant, yes, but also illiberal forces within his own university, including those concentrated in the divinity and public-health schools, the hot centers of extremism after October 7, 2023. [Rose Horowitch: What